Want to get involved in the sustainable fashion movement but are not sure how?

Having worked as a junior buyer in the fashion industry, I have first hand experience of fashion supply chains. I became disillusioned with the practices of the industry and wanted to help make a change. What could I do as an individual and small business owner? How can I make a difference? Eager to learn more, I enrolled on the Fashion Revolution course in collaboration with Exeter University and Future Learn.

The course is designed to convert students into fashion activists. Starting with three garments in our wardrobe, we were asked what are our emotions behind them? why did we chose them? What do they mean to us? Then the more difficult task of finding out where they were made. The label states the country of manufacture but is that the true story? The country listed on the care label might only be the place the garment was finished, including stitching in the care label. There are many processes involved in making a garment: Producing the fibre through to it being handed to us in a carrier bag over a shop counter. Considering each step certainly puts fast fashion shopping into context.

I contacted the brands of my three garments to ask #whomademyclothes? including the fabric. I didn’t receive a response from Levis or Topshop but Collectiff replied ‘We get fabric from our print supplier who get the greige from their Mills all based in China but we have no further information regarding this‘. They were able to tell me that the fabric was printed in China and the skirt also manufactured there. I wasn’t surprised by Collectif’s answer. I had read the comments of the students further ahead on the course than me and the majority had also been unsuccessful in finding out the true location of their garments, many not receiving a reply. A Fashion Revolution report from 2015 shares the statistics to support my research.

-

91% of companies don’t have full knowledge of where their cotton is coming from

-

75% don’t know the source of all their fabrics

-

Over 85% of companies are not paying their workers enough to meet basic needs

-

48% haven’t traced where their clothes are being made

I started my career as a Buyers Admin assistant, reaching junior buyer level at Arcadia, one of the largest fashion retail companies in Europe. Selecting a product for the range was similar to being part of a long complicated property chain with the customer being the first time buyer and the buyer being the Estate Agent. A buying team works with designers on the overall look of a range and individual garments. The buyer then briefs a manufacturing agent on the spec of the item, the quantity of the order and negotiates the cost price. The agent may own factories themselves but they may also outsource to other factories and this factory may outsource the order to another. The factory that produce the garments will not be the same one that dyes and prints the fabric. There will be another manufacturer who weaves or knits the greige (name of fabric before it is dyed or), yet another spins the yarn. Then there is the farmer or factory that produces the fibres. You can see why the supply chain is complicated.

I was concerned with the destination of the final manufacturing process as this affected the price. Global governments used to set quotas on imports and exports depending on where products were made e.g. if a garment was finished in Hong Kong, it would be cheaper than buying it direct from China (I worked at Arcadia from 1993 to 2000, this system was abolished in 2005). I might have known where the finished woven, dyed and printed fabric was from but I wouldn’t have known how it got to that state and certainly not where the fibre was grown. Sadly it seems that nothing has changed in the past twenty years and the fashion industry still has a long way to go before it becomes a circular transparent industry. Full transparency means the brand letting the customer know the origin of every stage of the manufacturing process.

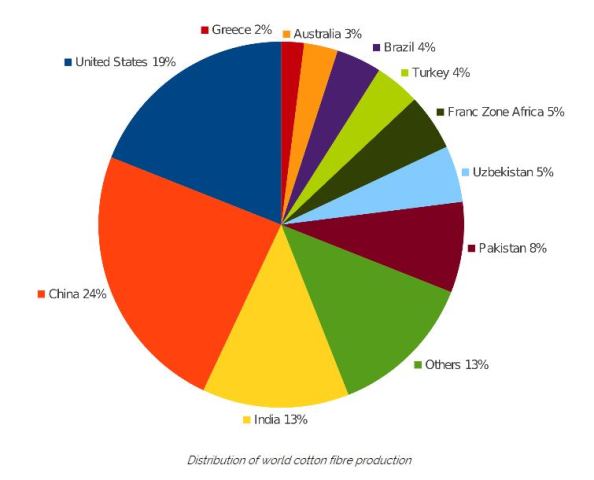

Back to the mystery of my cotton skirt! China is the biggest distributor of cotton fibre production. My skirt was made in 2016 and the above chart shows that two years ago China produced 5% more cotton than it’s closest competitor, the USA. Can I safely assume my skirt was produce in China from fibre to finished skirt? According to a recent article from the Business of Fashion ‘Chinese firms like Kerr have come circle by moving their yarn and textile mills to American states, like South Carolina, where cotton is relatively affordable’. This New York Times article explains ‘From 2000 to 2014, Chinese companies invested $46 billion on new projects and acquisitions in the United States, much of it in the last five years’. The article elaborates that the US Government issues subsidies to US cotton growers resulting in it being cheaper to grow cotton in the US and ship it to China for processing than it is to grow it in China.

‘Rising costs in China are causing a shift of some types of manufacturing to lower-cost countries like Bangladesh, India and Vietnam. In many cases, the exodus has been led by the Chinese themselves who have aggressively moved to set up manufacturing bases elsewhere.’

The New York Times, 2015

The issue for me isn’t the nationality of the owners of the factories, it is about traceability. Fashion Revolution encourage us to investigate the human story; who were the people who picked the cotton? spun the yarn? wove the fabric? Were they paid a living wage? Were they given enough breaks and not expected to work 12 hours without stopping? Did they have enough protection from the chemicals most cotton farmers use to grow the fibre? Was there child labour involved? Did they experience sexual harassment? How can a fashion brand answer these questions and endorse corporate and social responsibility if they don’t know where the fabric has come from or can’t be assured which factory is making their garments?

As a customer and an ex-employee within the fashion retail industry I encourage everyone to ask these questions. If we put pressure on our favourite brands, buyers put pressure on their manufacturers and agents, eventually the industry will become transparent. Without us asking these questions, the Fashion Industry will carry on for another twenty years without changing and the lives of textile industry workers will be negatively affected.

To find out how you can get involved, go to the Fashion Revolution website. Fashion Revolution was set up in 2013 in response to the Rana Plaza disaster where 1138 People lost their lives whilst working within the textile industry. For six years they have been campaigning for better working conditions for textile industry workers. Their week long campaign, #whomademyclothes runs every April to mark the anniversary of the disaster. This was the second year of the Future Learn course and I think they will run it again, Find out more here.

The fabrics I sell at Olive Road London are vintage and pre-loved. It is common for me to source fabrics without any labelling and I make an educated guess at the composition. I don’t know when or where they were made or by who and therefore cannot check if the textile workers were fairly treated. By selling vintage fabrics I am addressing another issue within the fashion industry – textile waste. Textiles are discarded as soon as they are cut into shapes to make our clothes, short lengths are discarded by large manufacturers, known as dead stock. I source and refresh these fabrics so you can reuse them, recycle them into a new garment or soft furnishings. Recycling what we already have prevents textiles from reaching landfill and taking decades to degrade.